This essay is an ongoing product of discussions and conferences among Filipino Marxist and national democratic youth organizers as we attempt to deepen our understanding of Social Investigation and Class Analysis (SICA) work. It is in this light that not only is there a necessity to underline the importance of SICA work for the Filipino youth, but also to give some pointers on what to look for, what to watch out for, as well as have theoretical discussions on social classes.

Introduction: No Investigation, No Theory, No Movement

Among Marxist circles, Lenin’s phrase “without revolutionary theory, there can be no revolutionary movement,”1 denotes the importance of studying and adhering to the proven principles of waging a working class-led mass revolution. These principles, however, do not “come from the sky.”2 They come from the trial-and-error practices of people trying to liberate themselves. The principles were never derived nor intended to be treated as a catechism or dogma; they were conclusions derived from historical analysis, and proven in the crucible of successful, partially successful, and failed revolutions. This is why Mao Zedong always emphasized the need for social investigation; despite the many lessons of the Russian experience, there would always be particularities that could not be solved by the one-sided emphasis of general principles.

We belabor this point because it returns us to one of Marx’s lines in his critique of Hegel: “To be radical is to grasp things by the root of the matter.”3 It is not good to be unable to name the causes of our triumphs and obstacles; it is also not enough to label a phenomenon as a symptom of an “-ism.” General solutions cannot fix particular problems. Our understanding of theory should not simply be general abstraction, but particularized and concrete based on up-to-date and verifiable information as well. The only way we can do this is if we take social investigation seriously.

There are principles derived from a praxis-oriented scientific outlook, and “principles” that Mao Zedong blatantly calls book-worship.4 We reiterate: blanket and general statements cannot solve the particularities of a problem, from the international to the local-organizational scale.

Thus we can complete Lenin’s phrase: without social investigation and class analysis, there can be no living and scientific revolutionary theory, and there can be no real revolutionary movement.

In fact, we will go as far as to ascribe ideological revisionism, political opportunism, and disorganization to incorrect or lack of regular social investigation and class analysis. We cannot simply villainize those who have made grave errors, as the documents of organizations show us that contradictions arise from an incorrect or incomplete view of objective social reality grounded in class struggle. The spinelessness that Lenin ascribes to opportunism is not a personality trait of the individual; opportunism is not a problem of identity, of lacking conviction. To demonstrate our point, let us examine some examples in revolutionary history of the past century.

In the Philippines, despite having a correct fundamental understanding of the role of the working class as per the Marxist-Leninist training of Crisanto Evangelista, and the PKP-1930, an incomplete grasp of our semifeudal conditions and the failure to develop Marxism-Leninism along these concrete conditions (without even minding the organizational troubles in leadership and structure), would lead to policies that effectively self-sabotaged the organization.5 Things were so bad that by the time Jose Maria Sison joined in the early ‘60s, there was barely any functioning party branch. It is no wonder that one of the enduring works of the first rectification would be a work on Philippine society—its classes, their development, and a program towards liberation.

Looking at the ‘80s–‘90s, the bloated number of armed guerrillas, an uncritical assessment of “urbanization” of the general population, the downplaying of agriculture in actual market share at the heart of our incontestable export-orientated/import-dependent economy, and some changes in percentage of the traditional peasantry . . . all of this lead to the notion of preparing for a premature urban insurrectionism, which objectively cost the movement political and organizational setbacks.6

Returning to the Chinese revolutionary experience, before Mao Zedong effectively took the helm by the late 1930s, the CPC was wrought with a diluted analysis of Chinese society, resulting in multiple setbacks on all fronts of the struggle. From Chen Duxiu, Qu Qiubai, Li Lisan—the 28 Bolsheviks of Wang Ming and Bo Gu—the overestimation of the Chinese working class in a semifeudal society, and the incorrect handling of contradictions among the people, (particularly within the already stratified peasant class),7 resulted in several grave errors.

The same goes with the struggles Lenin had with revolutionaries both in Russia and in the Second International. Within Russia, Lenin poured over 500 books and much statistical data in The Development of Capitalism in Russia8 to prove the incorrect theories of the Narodniks, who one-sidedly emphasized the role of the peasantry in leading a socialist revolution. He was able to show how capitalism had internally developed within the tsarist empire and was in the process of dispossessing the peasantry towards a worker existence.

He fought against those in the leadership of the Second International, who argued either for a peaceful evolution from capitalism to socialism or a one-sided pacifist stance to the war. He, like other noteworthy contemporaries such as Luxemburg, saw that monopoly capitalism only exacerbated the instability and uneven development towards crisis—and that unless the proletariat led the effort to not only end the war, but to point their guns at the reactionary state, the wars, historically, would not come to an end.

Documents providing a scientific social investigation and class analysis of affairs have proven to be more theoretically and practically decisive than any pure speculation about society or invective to create movements against oppression and exploitation.

On Social Investigation

Once More on Knowledge

The basis of our epistemology draws on Marxist theory, wherein knowledge is derived from social practice. Other than the importance of actually diving into the world practically, there is an often-forgotten implication to the notion that to better understand a thing is to be able to change it, (to mediate what is sensible, both in the mind and in the external world). The implication here is that our knowledge in the present is actually of something that has passed (the thing’s past state), from which we can infer/deduce our present, as well as possible future trajectories.

On the socio-historical level, the above implications mean that social revolution is the means by which humanity slowly becomes self-conscious of how society and the world works. On the organizational level, it means that SICA work must be done regularly. As researchers and investigators, it means that while there is a reality that exists out there, our knowledge is the mediated construct where this reality and our engagement with it intersects. This reemphasizes the need for rigor, collaboration, corroboration, and testing in all our work. This also does away with the notion of scientific objectivity, which treats society and its contents from a distance.

On the interpersonal level, to gain insight to one’s self and others is to mediate the experience of the self and others in thought and action. This means that to keep investigating is to really immerse oneself in society, which results in a dialectic of transformation. If we merely repeat the same resulting information without transforming the conditions, it is possible that we have not yet studied reality in its essential parts. At worst, we have only repeated in speculation and words that there exists a correlation and/or causation between concepts such as poverty, corruption, and other terms, without concretely verifying for ourselves how these things actually relate to one another.

On a practical level, SICA work requires executable plans in order to change conditions on the minimum and maximum levels, which bourgeois academic institutions barely try to accomplish in their efforts to study communities or social problems. Whether they be self-proclaimed Marxists or liberals, an analysis that could not be acted upon, even on a concretely minimal level of socio-civic activities, is an analysis stuck in the purgatory of unverified recommendations and propositions.

On a theoretical level, SICA capacitates us to combat subjectivism of all forms, for in a sense, all verifiable knowledge turns out to be a practical tool. Every breakthrough in theory and practice develops such that while it overcomes current obstacles, the rationale in older and less developed praxes are forgotten, and one-sided fixations in theory and practice also emerge. This becomes apparent in the future, as the dialectic of knowledge (theory and practice) develops.

Methodologies

Marx’s method of analysis begins and ends with social totality and the dialectic of the part with the whole. Every social phenomenon is an intersection of these contradicting points of view. This social totality that Marx studied is shown to be a historical subject and object of study.

To study social totality is to concretely study qualitatively and quantitatively. We uphold the notion that everything that exists can be measured and is expressed as a quantity of a certain quality. Matter possesses definite measurable quantities of qualities like hardness, density, volume, etc. The same is the case for social phenomena.

Qualitative data is generally based on impressions. As impressions begin with fragmented, particular, and individual experiences, we should take care to ensure that we have exhausted all possible outlooks on a matter. Concretely for an organization, this means making painstaking efforts to invite the maximum number of people in the organization when it comes to assessment and resolution building. For the individual organizer, this should challenge us to really know the people whom we organize—not to treat them as simply pawns to be organized, but genuine people who objectively have interests and goals that intersect with our own—to really spend time knowing them in their daily lives and struggles. If we do not allow ourselves to know people, we separate ourselves from the people we claim to serve. Every true activist and organizer must challenge themselves to walk the extra mile to sincerely know the masses. The richer everyone’s experience is, the easier it will be to arrive at an objective and all-sided view of the manner.9

If possible, we should find ways to translate qualitative impressions into quantifiable concepts or data.10 One way is extracting common words or phrases from a given set of impressions. Another is to derive a measurable process or relationship between the variables. Providing testable “if you do X and Y given Z and W; then A and B will happen” statements, are helpful to find what is actually a necessary component/relationship governing a given social phenomenon. One thing this approach does is it makes our investigation and plans more scientific in the sense of measurability, forcing us to look at the things we can control that are necessary for things to work out.

When it comes to the method of analysis, we simply break down a phenomenon into its different parts, looking at how each part works in relation to the whole. But we must remind ourselves that since things are constantly in motion, we need to analyze the inner workings and contexts of a phenomenon in development. In concrete terms:

- Synchronic analysis: looking at the interrelatedness of the thing/phenomenon observed at the moment. These may include:

- Geographical features

- Technological or logistical inventory

- Cultural, political, and scientific contexts

- Population sizes

- Diachronic analysis: looking at the evolution or development of a thing. Such as:

- Migration Data

- Shifts in Politico-Economic conditions (industrial revolutions, certain policies, etc.)

- Development of practices or material culture

- Dialectical analysis: understanding a phenomenon as several unities of opposites, and how these contradictions play out in the development of it (a proper synthesis of synchronic and diachronic analysis). For example:

- Understanding the general essence and the particular appearance of a phenomena, and how those two relate to each other

- Understanding the necessary element, the primary contradiction, and its principal aspect

- Seeing the basis for class alliances and betrayals

- Tracing the possibilities for how the phenomenon/situation can/will change based on how the contradictions develop

- The transition from quantitative to qualitative change, both gradually and at its rupturing moment

By first understanding what there is and how it emerged in time, one can analyze it by breaking it down into its constitutive parts, then synthesizing how it actually works.11

On Class Analysis

Social Investigation done as mere collection of facts and statistics without an analysis of classes (in terms of developments and balance of forces, and tested in the crucible of struggle), is incomplete from a dialectical understanding of knowledge, and unusable from the standpoint of practical revolutionary politics.

Class is the central question and ground from which various struggles among the left have emerged. When we say that all revolutionaries begin the development of their revolutionary theory and practice with social investigation, the character of this examination always returns to resolving differences in class analysis.

The first major point any Marxist should remember is that class is not separate from historical development; it is not a metaphysical structure, or a great chain of being that has always existed in human history. There is no ahistorical structure or force that determines social hierarchy. Second, class is also not reductively one’s income bracket or source of income, as it is commonly depicted in the statistics of bourgeois states.

Before the 18th–19th centuries in Europe, a systematic analysis of the origins of class, social stratification, and inequality was rare. In Classical Persian and Greek literature, we find that there is the notion of class distinction similar to role-playing games—a segregation based on ability, institutionalized at some point by such-and-such rulers. Property is only hinted at by some like Aristotle.

It is with the European social contract thinkers in the 16th century onwards that the relationship between social class and property is more systematically explored. As a type of agrarian capitalism and early industrialization evolved in 16th century England, the relationship of private property and social inequality manifested in the writings and actions of anti-feudal movements.12

The concrete struggles of the working class in 19th century Europe, in victory and defeat, were able to confirm Marx’s line of thinking with regards to the goals of each class and how the class struggle in the capitalist era would be best carried out to achieve socialism. However, as evidenced in the struggles of communists a few decades after Marx’s death, there would still be questions on what class really meant in the Marxist sense, and how to develop a political program based on the characteristics and dispositions of classes.13

So, What Is Class?

As Marxists, we should resolve these theoretical concerns by going back to concrete history. And history reveals to us that the variance of modes of existence can be traced in the development and entanglement of people according to certain praxes. A social class, or social being, is created by and creates praxis (understood as the combination of concept/idea and practice). This is observable by what the social group typically does/or the range of their activities and how much of their existence is spent engaging in these activities; in short, their praxeological entanglement.14

But human actions do not exist in a vacuum. They are always grounded in the aggregate of objects and people who augment their ability to act on the world physically and socially.

Thus, class is the social stratification of modes of existence grounded in praxeological entanglement. And while praxes have existed and developed even before class societies, it is our praxeological relationship to the productive forces (or generally the aggregate of human-object relations) which serves as the historical ground for classes to emerge and continue (and by extension, this dialectical process of complexity of praxis and general development of living standards). But the qualitative breaking point that ushers in the age of class society emerges when there are developments in the usage of productive forces in order to subjugate a group of people to extract various forms and degrees of value. Thus, to understand the core of class society is to grasp the particular praxes that enable the extraction of value. History will show us that the whole process of extracting value and maintaining a society on this kind of production is inextricably linked to praxes of appropriation, participation in key forms of social production at the historical epoch, and inevitably systems of ownership.

In essence, of all the praxes with which humans are engaged, those that deal with the subsistence of that society, take precedence over, or are more primary than others. It is from these praxes that other ones emerge or develop parallel to it and are impacted. And it is from these praxes that we can fundamentally begin to understand class.

In the Philippine context, the CPP’s basic party course states that the primary basis of one’s class is their economic standing, understood through an analysis of their ownership of the means of production, role or participation in production, and their share or appropriation of the value produced in society, as well as the means they use to do so.15

Some questions arise here:

- Who owns and controls the means of production? How much ownership/control does each social class have?

- Do they participate in production? If yes, is their participation essential to the whole of society?

- How much do they earn? What means do they use to gain their income?16

There are many ways to answer the above questions on a local, regional, national, and international level. We can find methods from the discussion of social investigation previously discussed. But generally, we can use diachronic and synchronic ways of doing this.

In terms of ownership, we can use various methods to map out forms of productive forces like plantations, real estate, factories, and who shares in owning these—and especially in the Philippine context, possible familial connections. In terms of participation, we can use quantitative and qualitative approaches of inquiry about the conditions of the various roles in production. In terms of appropriation, we can look at quantitative and qualitative inquiries on wealth/income distribution, as well as find out the various ways in which surplus value is extracted in local companies, industries, or even entire global value chains.

Now, this is not the only thing that is mentioned in the basic party course. Another factor is political stance. Questions asked here are whether the class or individual is an oppressor/oppressed, ruling/ruled, revolutionary/vacillating/reactionary.17 Tracing the historical political positions taken up by a group, community, family, or person could be an empirical way of undertaking this task.

Overall, economic standing and political stance are the markers looked at when doing class analysis. However, there are more things we can extract out of this, and certain cases where it requires more examination—particularly with the gap between one’s economic standing and their political affiliations. How is it possible for entire class factions to politically betray classes they are generally aligned with? What about the military, composed of members from all classes? How can we use an analysis of their economic standing to concretely understand their political role, especially in the historical instances where they sided with the masses? These questions are answerable by gaining experience of concrete analysis of these groups in their particular contexts. However, from the information at hand, we can expand this formulation of class analysis.

In the latter prefaces to the Communist Manifesto18 Engels says that while the essence of the text remains correct, the course of the class struggles worldwide provided many lessons regarding nuances of this struggle. Indeed, the nuance of struggles from 1848 to 1871 particularly arise when one looks at the alliances and betrayals among the various classes, or how certain sections of the working class took on more leadership roles in the struggle, or even how the general masses were mobilized in different forms of fighting.

To solve the question of the concrete bridge between economic standing (understood for now as focused on analysis of ownership, participation, and appropriation) and political stance, is to see the affinity or alignment of class interests based on the former leading to their positions in the later.

Class Alignment

In Marx’s various texts on the class struggles in France,19 we can see how class political alignment is grounded on the similarities or closeness one class position has with another regarding their praxeological entanglement, primarily on the praxes of subsistence, or what we looked at when investigating economic standing.

Among the initial praxes of ownership, participation, and appropriation, appropriation is the most visible when we look for the extraction of surplus value; we find that this is merely the final step that is actually grounded in property relations, or essentially, ownership. This is why a commonsensical notion of class is to divide society into haves and have-nots, a notion rooted in ownership. Generally, ownership can be said to be directly proportional to appropriation, as the more you own, the more surplus value you can extract. The difference is qualitative: what type of productive property do they own, and what are the ways in which they appropriate value?20

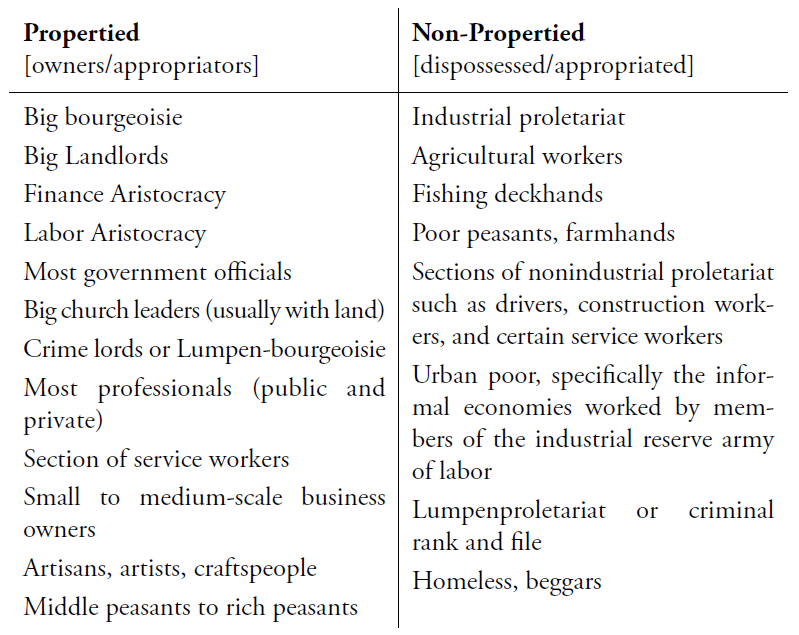

The primacy of ownership is also why, despite its etymology denoting the political and economic ascent of the then middle class, the term bourgeoisie now refers to the elite/big owning capitalist class, which is distinct from a similarly elite but landowning class. In the following table, we can categorically divide most of the social groups in the Philippines, into the axis of propertied/non-propertied (coalescing ownership and appropriation for now—we will discuss this further later); yielding the following:

Of course, in reality, the different classes exist on an economic spectrum of propertied and non-propertied. Politically, history shows that class struggle did not always play out where the whole propertyless were united against the propertied and vice versa.

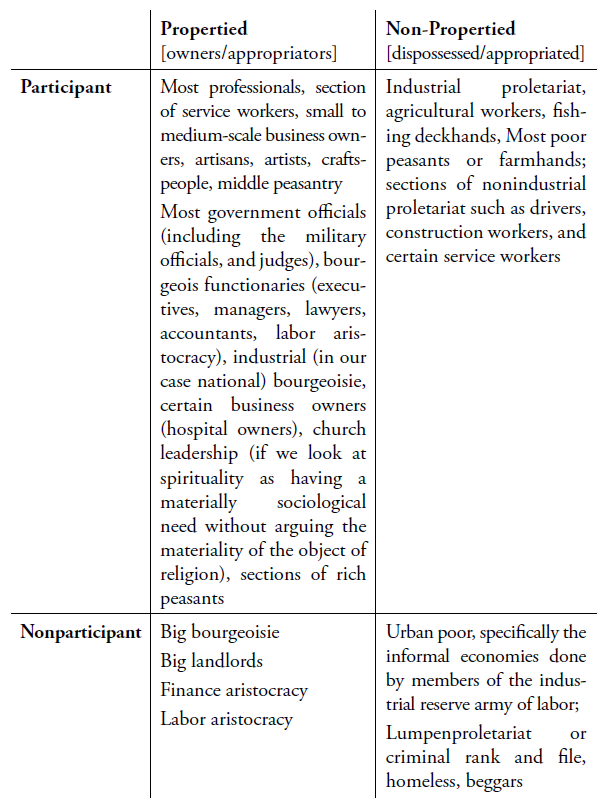

Moving forward, we add the dimension of labor participation to our analysis. Revealing the actual participants in the labor process shows how certain sections of the petty bourgeoisie and the peasantry can be aligned with the industrial proletariat. Meanwhile, on this axis, most of the industrial reserve army who enter into informal economies are divorced by a degree from the proletariat. We can categorically divide them into a table which might look like this (again noting that these things concretely lie on a spectrum):

We can see how the table above shows the basis for how the industrial proletariat has a solid basis to link up with the poor peasants (who constitute the majority of the peasantry); and how there is a structural basis for those of the propertied classes to ally themselves with the proletariat.

However, we still miss important details when looking at economic standing: what the CPP called the “essentiality” of a class’ participation in social production as a whole. The essentiality of any praxis, such as types of labor or production, can be understood as how necessary this praxis is in history. The necessity of a certain type of participation in society is something that changes. There are certain vocations that are deemed crucial at an earlier historical epoch than they are now. In the dialectical development of history, the necessity of these vocations transform, may take on secondary importance, or wither away. An example of this is the role of religion and how crucial it was not only for ideological control, but overall knowledge production translating into findings (both from and against the church) that would improve productive forces.21

Of course, when looking at the concrete facts, we see that the necessity of something in history is not linear. As early as Marx’s time, the essentiality of national standing armies and the church were already seen as not only unnecessary, but deleterious. And yet, we see how the military industrial complex has played a role in developing productive forces such as the internet, and maintaining the imperialist state apparatus as a whole. We see how various religious sects transformed to adopt revolutionary struggles, moderate but critical politics, or firmed up their reactionary nature. And from a larger perspective, we have seen how capitalism has adapted through various forms and means against its internal and external crises.

So how do we measure the basis of necessity?

From the theoretical aspect, a study of how capitalism develops higher forms of socialized and automated labor while increasing private monopolization is crucial in understanding how the economic and political workforce might develop. More than 200 years later, Marx’s thesis on capitalist development remains correct. Thus, from a historically objective perspective, capitalism and the functionaries blocking the leap to a post-scarcity communist society, are on the trajectory to be nonessential.

From a concrete aspect, we should look or conduct studies on how the economic, political, cultural, and military institutions are being reorganized, on what basis, and whether their members are increasing or diminishing. There are several methods to conduct these studies, and reading such papers would benefit us in having an understanding of how a certain sector is developing. But generally, by conducting surveys and looking at available data, it is possible to find a rate of increase or decrease in a specific quality we are looking for.22

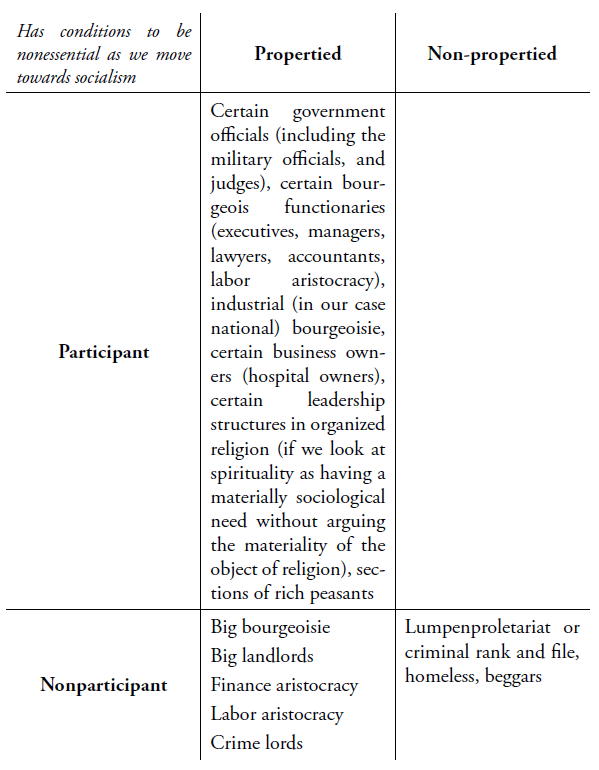

We know for a historical fact which classes are crucial in building socialism, and which ones are most likely to be erased or transformed. For the most part, it is clear that the activities of the lumpenproletariat have no place in an advanced form of socialism, and that socialism creates conditions for them to wither away.23 We can also safely say that the superfluous sections of the propertied class who do not participate in labor, or direct labor to disgustingly luxurious or downright wasteful projects for the benefit of a few, can also be nonessential at this point of history. So classes such as the finance and labor aristocracy, big landlords, comprador and industrial bourgeoisie, are all on this line.

However, we know that part of the basic theses of Marxism is that, under capitalism, all classes are historically being subsumed by the bourgeois or proletarian camp. Hence, there will be sections of the middle class, even those participating in social production, who will be transformed or will lose their basis to exist as they are now. With what we know from the attempts at worker-led people’s governments, reorganization of the state as the productive forces/infrastructure develops to get rid of bureaucracy, gives the condition for many governments, military, and judicial positions to be rationalized.24 The same goes with bourgeois functionaries such as executives, accountants, lawyers, and law enforcement (and most possibly transformations in legal structures when major leaps have been made in reorienting property relations and restorative justice).

On the flip side, most class positions who participate in social production who are dispossessed, or who demonstrate having important functions in the first few phases of beating monopoly capitalism and building socialism, could be considered historically necessary in the current and coming age.

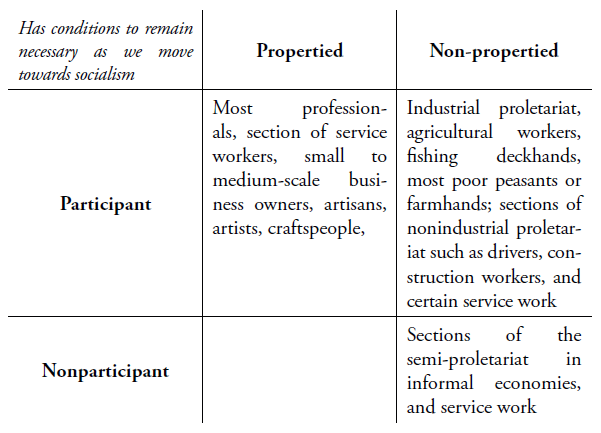

In terms of a table then, we could have something like this:

These tables show us that certain class relations or positions have an affinity with others depending on certain lines. The majority of the peasantry have a basis to unite with the industrial proletariat, as they have a basis to unite on property, participation in social production, and social vitality. However, the middle and rich peasants, being propertied classes, have a basis to not unite with the workers. The same goes for the lumpenproletariat who can unite with workers on the basis of property, but only on this matter. Certain sections of the military and the state have joined the working-class cause, but are just as removed in affinity with the proletariat as the lumpen. Whatever actual political stances they take, such stances will always have their class basis on the affinities or alignment to the different positions.

Thus, for the most part, class analysis usually looks at the above praxes when studying the general and concrete phenomenon of class. However, we know that this presentation is not the full extent of how class impacts social relations, and that the praxes of ownership-participation-appropriation-essentiality acts as mere praxeological basis for political stance. Historical materialism also teaches us how there are praxes, while products of property relations, that affect these relations concretely.

Class Articulations

One thing about the 20th century “Marxisms” or “critical theories” of the petty bourgeoisie, is that they limit, or fixate themselves to an analysis of what Marxist vocabulary calls, the superstructural. With how vaguely various people interpret the meaning of economics, politics, and culture, there is a danger of being reductionist, to relegate praxes that at first do not manifest economics or politics as cultural or even superstructural. The same goes for treating economic praxes as developing in isolation without developments in science, in laws, in discourses of what it means to be human, etc. There is the danger of a mechanical understanding of these praxes as the economy-base-content and politics/culture-superstructure-form without realizing the duality that is their distinctness and interconnectedness.

What is clear is that there are praxes that developed independently or parallel to the praxes of subsistence, but in the final analysis, are grounded to subsistence. Most of these are praxes of sensibility (i.e., customs, aesthetics, semiotics, interpersonal relationships, etc.).25

The interconnectedness of these praxes explains the notion that everything is marked by class. Another way of saying this is that depending on the inclusivity/exclusivity of the praxis (grounded in how they are organized, as well as questions of accessibility due to ownership-participation-appropriation matters), various classes take part in the praxis and vie for making it their own, for their benefit (regardless if others will gain too). It is just that those who are liberated by time and resources have more ability to change the praxis, which develops the praxis along the conditions and interests of that class.

Another way we can state this is to call these activities the praxeological articulations of one or several classes. Every human sensibility is an articulation of their creativity and labor, conditioned by the thoughts-practices and limitations-freedoms in time, resources, and labor. But just because a class articulates itself or constantly renews its mark on a praxis, does not mean that these articulations in themselves are the class itself, or a substitution for a theoretical and practical critique of private property. Thus, we see how praxes like race, gender, religion, or spirituality, were always avenues for class positions to articulate themselves, but are not themselves the core of the class’s existence in itself.

An important aspect of the emergence of these praxes is the way in which they “fold back” on each other. One has to take into account that class is a phenomenon that touches praxes that are not directly connected to social production, and yet have a way of folding back on it towards transformation. Class is a total category encompassing all society.

While it is true that in general, the development of the productive praxes and especially of the productive forces have a large-scale effect on the twist and turns of history, the experience of proletarian movements and socialist constructions have demonstrated the role of the secondary praxes—of customs, aesthetics, and discourses, which provide the appearance of how social relations among people come to be.26

Changes in the productive forces do open up new ways of living and relations among people. And these praxes are inherently the product of the possibilities/limitations and aspirations of the contending classes—hence praxes with classed articulations or marks. At some point, these praxes gain some relatively stable features (for the time being) as well as theoretical interventions. Thus, the latent contending class marks on the custom, aesthetic, or relation becomes manifest on the level of discourse. As such, we see how in primary praxes like property relations become manifest in certain fields like law, and that it also plays a role in how discourses and practices in religion proliferate, mesh, and contradict each other. But by waging struggles in the fields of law and religion, for example, it is possible to trace a way back into the war against private property. This is what it means to understand the “folding back” of praxes.

When taking into account the criticisms of revolutionary teachers and leaders, we will see that it is through the combination of struggles in how we perceive, act, conceptualize, and in revolutionizing social production that we can effectively transform class relations. By understanding the ground for alliances (alignment of class interests), and of the contention of classes in other praxes (practices/discourses articulated through classes)—as well as the dialectical relationship of these two, and how they are actually the dialectic of human history and awareness developing—we can move on to the final aspect of class, which is class consciousness.

Class Consciousness

Class consciousness is essentially the most locally concrete and historically particular form of the dialectic of class in a given society. It refers to how self aware the collective or individual is of their being a historical subject, of the dialectic of classes, their position in it, and the intensity of their participation in this struggle.

This consciousness is not something “innate” in all humans. If we remember the earlier discussion, we saw that the notion of class as a difference in property relations only fully arises at the advent of capitalism.27 So, while capitalism is the objective basis for a more proper consciousness of class to emerge, how does it develop concretely? We need only return to the past few centuries of class struggles to answer this.

Everyone begins from a partial or subjective consciousness of class under capitalism, both from the limitations of our individual experience, and the general dominance of reactionary ideas. Hence we all begin in some form of false/incomplete/subjective consciousness. Thus, the point is to gain knowledge. To gain knowledge of political struggles is to understand the class struggle in its parts and as a whole. This is why it is possible for people of non-working-class origin, through their participation in class struggle, to grasp capitalism’s contradictions concretely, and thus begin the process of betraying their class origin.

This notion affirms what we discussed earlier: revolutionary ideology is the product of the dialectical process of individual participation in a growing collective immersed in class struggle. In the final analysis, this is the basis for class struggle always manifesting itself acutely in avenues for theory, and organized bodies, from which the war is carried out. This means that the problem of advancing class consciousness is actually a problem of advancing class struggle holistically.

General Critique of Class Rejectionism

If we examine the past century, we will see that one of the ideological grounds for opportunist politics is the poor understanding of class consciousness and its relation to the class struggle. On the one hand, we have people who have simply rejected the category of class as the principal driving factor in social change. On the other hand, we have those who look at class in a metaphysically absolute manner.

The rejection of class as a primary category in understanding our current society is the standpoint of those belonging to the propertied class, who might have been driven by anti-capitalist sentiments, but could not concede to the decisive role of the proletariat and of total revolution as the way forward. The petty bourgeoisie, who developed their various versions of liberalism and anarchism are the original products of this viewpoint. Various fundamentalist politics that tie their liberation struggle to an ahistorical view of their communal identity outside of class, fall in this camp. And it is clear that when class is taken out of the equation, myths and symbols have been used to fill the hole in the ahistorical categories these forces espouse; such is the case with fascists and various religious-national fundamentalist groups.28

Another development in class rejectionism is the rejection that social inequality is primarily grounded in the structures of value appropriation, beginning at the production process, which is inextricably linked to praxes of ownership of socially productive property (the means of production)—and that this ground, while dialectical, is the primary problem in relation to other struggles.

We also see that these theories have become the backbone of uncritical collaborations with anti-people regimes and politically paralyzed interlocutors, despite their intentions. In essence, the ambiguity of how class can be operationalized (or on what grounds they will base their politics) has led to right opportunist deviations worldwide. To this category belong most of the post-structuralists, postmodernists, neo-Marxists, Marxist humanists, and post-Marxists that dominate Euro-American left-leaning theories.

In the Philippines, these class rejectionist ideas organizationally manifested during the ideological splits of the ‘80s–‘90s. Various rejectionists of the Marxist-Leninist-Maoist and anti-revisionist line, also rejected the Trotskyite adventurist line of Filemon Lagman, and created a sort of “third way” or “third force.”29 They sought alternatives that didn’t require a “Leninist vanguard party”; hence they resorted to different forms of social/liberal/popular democratic formations. Politically, they have served as direct mouthpieces for reactionary regimes they were allied with in the late 90s and 2010s. Of course, Marxists have no business uniting with revisionists and opportunists except tactically for certain issues. The same goes for the crypto-Trotskyites masquerading as Leninists, who fall under another category of not grasping class.

General Critique of Class Absolutism

At the times that class was rejected as an explanatory category for social ills, there were those who affirmed class struggle in the manifest, but were actually employing a metaphysically absolutist understanding of class, which was met with regressive results. In theory, it is Marxist to agree with these groups that class struggle is the primary struggle. But the common ideological mistake from these groups is both conceptual/theoretical and practical, with the latter being primary.

On a practical level, these groups possessed a fundamentally incorrect analysis (if they had an analysis at all) of the classes, balance of forces, and/or mode of production in their terrains of struggle. They understood that the content of revolution is class struggle, but they did not understand how class as a total phenomenon emerges as the intersection of various interests competing in various praxes, with their own hierarchy of primacy in society. They assumed that the workers inherently possess a revolutionary consciousness—for how can they betray their own objective interest?30

In pre-1949 China, dogmatism and empiricism relative to the balance of forces caused various forms of “left” and right opportunism. There were party leaders such as Qiu Qiubai and Li Lisan, who underestimated the role of the Chinese peasantry as the main force and consistently opted for insurrectionist strategies to be led by their worker-soldier armies. In theory, the leading role of the proletariat is unquestionable, but concretely, not strategizing based on the concrete conditions of semifeudalism in China was a failure to grasp the real principles of Marxism. Even after the Chinese communists took power, it was the erroneous understanding of class as something related only to the relations in production, and not the total relations and dialectics occurring in society, that would manifest in various revisionist thinking, backing the policies enacted even within Mao’s lifetime.

The same case can be found in the Soviet Union, wherein the notion of class had vestiges of being solved by politico-legal means and the development of the means of production, which would cause the CPSU(B) to believe that the USSR had reached classlessness by 1936.31 They misunderstood that class is concretely made by humans but has an abstract but total existence in how it remains in various praxes surrounding even the “logic” of institutions and machines. Classlessness could not be achieved simply by enacting laws on property rights, improving the machinery, or even educational discussions. Every human activity and way of thinking would have to be reexamined and sublated through the various struggles in all these fields.

In the case of the Philippines, the various crypto-Trotskyites and actual Trotskyites had grossly misunderstood the 48% concentration of the local population in urban centers by the early 90s. This, among other arguments, would be their reason for their analysis that the country was a backward capitalist society with feudal remnants—and thus pushed the agenda to change the course of the struggle towards insurrection.32 However, just like the other class absolutists who forced their adventurist agenda, they would soon retreat from the “left” to a right opportunist standpoint and one-sidedly divert attention to parliamentary organizing.

They subsume politics and class struggle to simply the acquisition of power to counter the reactionary classes. This muddle-headed view of politics, the relationship between class struggle and class consciousness, and the holistic existence of the class phenomenon, is precisely the basis for ideological revisionism and subjectivism, political opportunism, disorganization, and unprincipled class collaborations.

The Holistic Task of Class Analysis

Taken as a whole, class analysis is an abstracted understanding of concrete social totality, based on how many people groups are in qualitatively connected praxeological entanglements to various degrees: from praxes of subsistence (i.e., property ownership, labor participation, value appropriation, historical necessity of their position) to praxes of sensibility (customs, aesthetics, discourses, ethics, interpersonal relationships). It is holistic because class is a total phenomenon. It is synonymous with an analysis of history as a whole. Class is primarily understood based on an analysis of praxes of subsistence, but is not only this. Thus, class is how entangled or caught up people are with various ensembles of objects, people, institutions, and activities, which in the final analysis, are inextricably linked to social production and value distribution. You cannot find class simply inside one’s body or clothes. There is no gene in someone that gives them bourgeois or proletarian consciousness; it is the totality of dialectics happening in society.

From a revolutionary standpoint, class analysis must result in the creation of plans on how the given objective conditions can be used to advance the struggle of the proletarian-led masses towards the elimination of class—a struggle that is concomitant with the raising of class consciousness. Hence concretely, the goals should be:

- Politically: the mastery (both theoretical and practical) of the forms of the struggle; when to use each form, and how it relates to the other parts. All of this is gained through experience and assessment.

- Ideologically: to regularly produce and distribute a comprehensive and exhaustive social investigation and class analysis of the concrete conditions.

- Organizationally: to understand that the ideological and political task of raising class consciousness and advancing the class struggle concretely is done organizationally, and thus requires all efforts to uphold and improve the way in which democratic centralism is practiced by organizations.

Conclusion: Grasping the Thread of Struggle

When things are discouraging, efforts seem to be going nowhere, or various ideas are competing, through social investigation and class analysis, we will find the thread of struggle out of the present situation. The task after finding this thread is to grasp it firmly, because the dialectical method will show us how it is possible to turn any situation around, no matter how adverse. As Lenin wrote:

The whole art of politics lies in finding and taking as firm a grip as we can of the link that is least likely to be struck from our hands, the one that is most important at the given moment, the one that most of all guarantees its possessor the possession of the whole chain.33

Dare to Struggle! Dare to Win!

- V. I. Lenin, What Is to Be Done? (Paris: Foreign Languages Press, 2021), 24.

- Mao Zedong, “Where Do Correct Ideas Come From?” in Selected Works, vol. IX (Paris: Foreign Languages Press, 2021), 16–18.

- Karl Marx, A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970).

- Mao Zedong, “Oppose Book Worship,” Selected Works, vol. XI (Paris: Foreign Languages Press, 2021), 24–31.

- Communist Party of the Philippines, “Rectify Our Errors, Rebuild the Party,” December 26, 1968.

- Armando Liwanag, “Reaffirm Our Basic Principles and Rectify Errors,” Documents of the Communist Party of the Philippines – The Second Rectification Movement (Paris: Foreign Languages Press, 2023), 58–139.

- One could explore Mao’s ideological differences with various Party leadership pre-1940’s in John E. Rue, Mao Tse-Tung in Opposition: 1927–1935 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1966).

- V. I. Lenin, “The Development of Capitalism in Russia,” Collected Works, vol. 3 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1960).

- This means that we should factor in social activities as part of general political work (not a mechanical life of discussions, meetings, and demonstrations), if we truly recognize the importance of social investigation. This applies from the rank and file all the way to the leadership. Li Yinqiao, one of Mao Zedong’s personal bodyguards from the Anti-Japanese War, recounted in his memoirs entitled Mao Zedong: Man, not God, that even as the leader of a liberated China, Mao Zedong broke security protocols during his trips to inspect villages. After their vacations, he would ask his bodyguards to give reports on the conditions in their home provinces. (He wanted every guard to come from a different province so he could have some grasp on what was happening in different places.) Quan Yanchi, Mao Zedong: Man, Not God (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1992).

- Let us all try to get better at numbers. First, this means to always be taking notes on statements and experiences that can be analyzed later, having an updated system of tracking tasks and data, and being able to explain things in a logically computable and sound manner. In the simplest terms, any action or state can be translated into quantifiable statistics and probabilities. This isn’t to fetishize numbers, but to constantly challenge us to understand social reality from a concrete, computable, and materialist perspective.

- We can see synchronic analysis in how Mao Zedong spent a month in Hunan in order to give the evidence-backed refutation to the party leadership who thought poorly of the peasant revolutionary movement. He was able to detail the various types of struggles launched by the peasantry from economic and political ones to cultural ones, such as family relations. In fact, in all his major SICA-like articles and documents, he begins with an analysis of forces that exist, what they do, and from there, analyzes the various contradictions. Only then does he present his thesis on where the struggle ought to be going. The same goes for the format in which the CPSU(B) would generally structure its reports, beginning with international to local conditions, then what to do and how it went, and concluding with resolutions and tasks. Marx’s major works in analyzing class struggles in France from 1848–1871 (Class Struggles in France, Eighteenth Brumaire, Civil War in France), and of course Capital, exhibit this kind of analysis, showing the dialectics of things in history. His analysis of French politics showed not only the chronology of events, but the class basis and orientation which grounded the actions of each faction; why it would succeed and fail at every turn of the struggle, or why it would be supported or betrayed by other factions. With capitalism, he analyzed capital from all its particular sides; from how it emerges, how it is circulated, reproduced, and its historical trajectory to its perennial crisis of overproduction.

- These ranged from utopians like Thomas Moore, to moderates like the John Lilburne and the Levellers and to the radicals like the Diggers (who advocated the abolition of private property). By the 17th century, we note John Locke and Jean Jacques Rousseau, who argued that private property is the origin of social stratification.

- We can see that the internal ideological and political struggles of most revolutionary parties result from differences in the abstract understanding of class and the concrete balance of class forces in their fields of struggle. Leaders like Lenin, Mao, Stalin, and Ho answered questions of the party’s role, political education, organizational structures and dynamics, targets and methods of propaganda work, united front building and general strategic and tactical alliances, and the politics of actual class warfare, by grounding them to the development of class struggle through the dialectic of history.

- Marx confirms this idea of class: “In the process of production, human beings work not only upon nature, but also upon one another. They produce only by working together in a specified manner and reciprocally exchanging their activities. In order to produce, they enter into definite connections and relations to one another, and only within these social connections and relations does their influence upon nature operate—i.e., does production take place. These social relations between the producers, and the conditions under which they exchange their activities and share in the total act of production, will naturally vary according to the character of the means of production. . . . We thus see that the social relations within which individuals produce, the social relations of production, are altered, transformed, with the change and development of the material means of production, of the forces of production. The relations of production in their totality constitute what is called the social relations, society, and, moreover, a society at a definite stage of historical development, a society with peculiar, distinctive characteristics. Ancient society, feudal society, bourgeois (or capitalist) society, are such totalities of relations of production, each of which denotes a particular stage of development in the history of mankind.” Karl Marx, “The Nature and Growth of Capital,” Wage Labour and Capital & Wages, Price and Profit (Paris: Foreign Languages Press, 2020).

- Communist Party of the Philippines, “Mga Uri at Krisis Ng Lipunang Pilipino (Types of Crisis of in Philippine Society),” Batayang Kursong Pampartido (Basic Course of the Party), Dani Maribat, trans., 1984.

- Communist Party of the Philippines, Batayang Kursong Pampartido (Basic Course of the Party), trans. Dani Maribat, n.d.

- Communist Party of the Philippines, Batayang Kursong Pampartido (Basic Course of the Party).

- Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, “Preface to the 1872 German Edition,” Manifesto of the Communist Party & Principles of Communism (Paris: Foreign Languages Press, 2020).

- Karl Marx, The Class Struggles in France (Paris: Foreign Languages Press, 2022); Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (Paris: Foreign Languages Press, 2021); Karl Marx, The Civil War in France (Paris: Foreign Languages Press, 2021).

- Note that the discussion on the qualitative difference in ownership and methods of appropriation is of importance in the concrete and localized understanding of a classed society, especially when we run into modes of production like in semifeudalism, where the local industrial capitalist is superseded by landlords and even they, by the big comprador bourgeoisie—situations that require slightly altered political nuancing, but we shall discuss this below.

- On a related note, Marx talked about how the mobile guard during the French political struggles of 1848–1851 was essentially lumpenproletariat, whose decadence was essentially aligned with the interest of Louis Bonaparte (Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte). He would also mention how the finance aristocracy was essentially the propertied version of the lumpenproletariat, in their ways of acquiring pleasure and wealth (Class Struggles in France).

- For example, unemployment/employment in a certain work sector, military expenditure and troop deployment, religious disaffiliation, etc. These are concrete and measurable indicators for how society is traversing, relative to the balance of class interests vying for power.

- Historically they have gone either way to become revolutionaries or appendages to monopoly capitalism to fund counter-revolution, demoralize, and depoliticize movements worldwide.

- Charles Bettelheim, Class Struggles in the U.S.S.R. First Period: 1917–1923 (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1977), 164.

- And of course, a systematic study of all the methods of gathering data and understanding it in these would take up entire books. We could ask, however, simple questions such as: How did these praxes develop throughout history? What are their various forms today? What are the various messages found in these praxes? Who are the participants, distributors, and consumers of these praxes (even in a non-economic aspect)? Which class positions have these mostly served?

- Lenin, in What Is to Be Done?, critiqued the economism of limiting worker struggles to trade-union struggles, emphasizing the need for a party that would inject revolutionary theory into the workers and mass movements. Mao also wrote in Critique of Soviet Economics, of how the soviets one-sidedly mistook the development of productive forces as the focus of socialist construction, without giving careful attention to changing the relations among the people as a whole, and waging the ideological battles.

- Lukács also made comments on how a consciousness of class would only arise at this time, precisely because it is only in the historical epoch of capitalism that hordes of people are dispossessed and put into constant and fast contact with each other. Unlike in feudalism or slavery, where the praxes of subsistence are self-contained/isolated, the social consciousness produced sees social differentiation as primarily based on individual differences in skill/ethics, or alternatively, fidelity with some objective truth, philosophy, or religion. Hence, we observe that in the epoch where slavery dominated, slave rebellions largely consisted of getting away from the slave empire that treated the slaves poorly. Peasant rebellions generally consisted of struggling against their warlords, the most successful of which would result in them building their own ownership of the land. It is only when capitalism emerges and connects the various parts of the world through commodity-market relations and the reaction of feudal warlord consciousness, that the grounds to develop a concept of class as based on property relations, begins—even when the phenomena had been ongoing for centuries.

- It is a historical fact that Mussolini opportunistically used Sorelian syndicalism (which rejects historical materialism and class struggle), which lead to his version of fascism.

- Alecks Pabico, “The Great Left Divide,” The Investigative Reporting Magazine, vol. V, no. 2, no. April–June 1999.

- Putschist and adventuristic politics fit in this category as well. Without understanding how we must painstakingly struggle not only in direct politics and class warfare, but also in economic/socio-civic work and counter-discursive theoretical work, it is naive to assume that the peasant-workers will mobilize in a sustained manner.

- Armando Liwanag, Stand for Socialism Against Modern Revisionism (Paris: Foreign Languages Press, 2017).

- Lagman Filemon, “Counter-Theses,” 1994.

- V.I. Lenin. What Is to Be Done?